The RBA is following a slightly different path from its peers

Economic Policies, The Australian Economy | 11th January 2024

The Reserve Bank of Australia has come in for criticism for some quarters for its most recent rate hike (on 7th November). Although most RBA-watchers, me included, think that there won’t be any more rate hikes next year, the Minutes of the 5th December RBA Board meeting show that another hike was a live option at that meeting, and that it remains a possibility at the first meeting for next year (to be held on 5th and 6th February) – especially if the December quarter CPI, to be released on 31st January, ‘materially’ exceeds the RBA’s forecast (as did the September quarter one, precipitating the hike in November).

Critics of the RBA’s most recent move come from both the left (eg, the Australia Institute) and the right (eg News Limited’s Terry McCrann), and in between (eg Crikey‘s Bernard Keane and Glenn Dyer).

While the RBA has certainly made mistakes in recent years – most obviously, as it’s admiitted, the ‘forward guidance’ during (and after) the pandemic, that interest rates would remain at record lows “until 2024 at the earliest”, and, in my view at least, being too slow to start raising rates in response to the rise in inflation that was clearly under way by the second half of 2021.

But I think the criticisms of the RBA’s conduct of monetary policy since then are misplaced.

In fact, the RBA appears to be willing to tolerate inflation being above its target for longer than its peers, presumably in order to preserve as much as possible of the gains that have been made in recent years in reducing unemployment and under-employment.

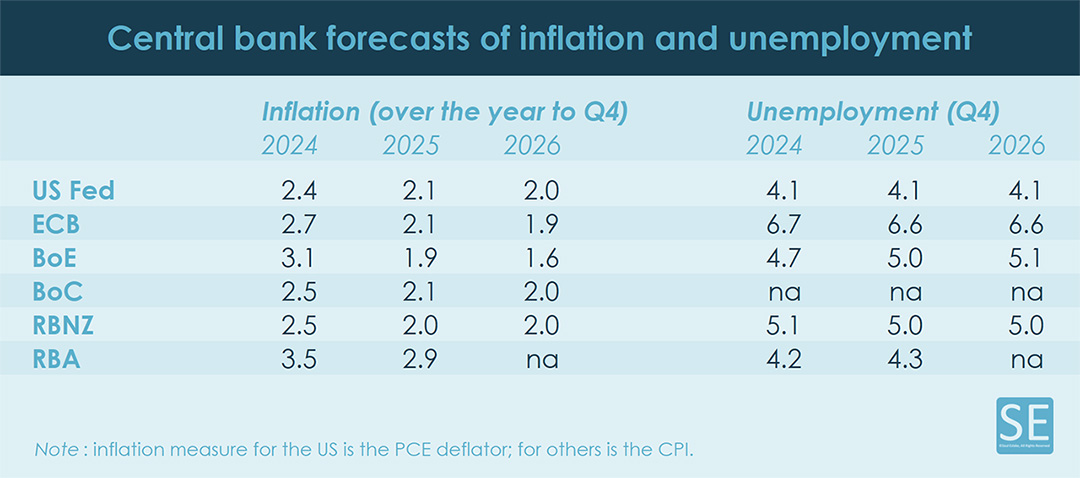

The following table sets out the latest forecasts for inflation and unemployment from the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand – what I would regard as the RBA’s ‘peer group’ – together with the RBA’s own forecasts:

The Fed and the ECB expect inflation in the US and the euro area, respectively, to be just 0.1 of a pc point above their target (in each case, 2%), by the end of 2025. In fact it seems likely that their inflation targets will be reached sooner than that. The BoE expects inflation to be below the mid-point of its 1-3% target band by the end of 2025; and the BoC expects inflation to be just 0.1 pc above the mid-point of its target band, also 1-3%, two years from now. The RBNZ also has a 1-3% target range for inflation: it expects inflation to be back within that range by this time next year, and down to the middle of that range by the end of 2025.

The RBA has a slightly softer target than its peers – 2-3% per annum, with the most recent Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy placing more emphasis on meeting the mid-point of that target band than earlier agreements on the conduct of monetary policy between previous Treasurers and RBA Governors.

But the RBA doesn’t expect Australia’s inflation rate to be back to the mid-point of the target range until some time after the end of 2025. Indeed, it only expects inflation to be just 0.1 pc point under the top end of the target range – and almost a full percentage point higher than in the US, the euro zone, Canada, the UK and New Zealand – by the end of 2025.

The RBA, like the Fed, has a ‘dual mandate’ – that is, it is required to conduct monetary policy with a view to sustaining ‘full employment’ as well as low and stable inflation. The most recent agreement between the Government and the RBA Board defines full employment as “the current maximum level of employment that is consistent with low and stable inflation”.

The RBA Board seems, in my view, to be taking this mandate seriously.

It is forecasting a rise in the unemployment rate – but one which is likely to occur overwhelmingly as a result of people entering the labour force (as migrants, as recent graduates from education or training, or after a period outside of the labour force caring for children or other relatives) taking longer to find jobs, rather than as a result of people with jobs losing them.

It’s also worth noting that although the RBA has raised rates more often than its peers – because it meets more often than them (although that will change in 2024) – it hasn’t raised them by a larger amount or to a higher level than its peers.

On the contrary, the RBA’s cash rate, of 4.35%, is lower than the equivalent rates set by its peers – the ECB’s 4½%, the BoC’s and BoE’s 5%, the Fed’s 5¼-5½%, and the RBNZ’s 5½%. One reasons for that is of course that changes in the RBA’s cash rate are transmitted more quickly to the ‘real economy’ than changes in other central banks’ policy rates in their economies, because of the preponderance of floating rate mortgages here (and the higher level of household debt relative to household income).

But I think it also underscores the point that the RBA isn’t trying to get inflation down to its target as quickly as its peers.

I should be clear that I am not criticizing them for that (although others may do).

If I’m right, and if the RBA’s forecasts are right, a likely corollary is that interest rates may come down later, and more slowly, than in other comparable economies. For now at least, I think the RBA’s cash rate could remain at its present level of 4.35% throughout 2024, even the Fed and the ECB, and probably the BoE and BoC, will likely start cutting rates later this year.

Of course, the RBA’s forecasts could be wrong.

The Commonwealth Treasury certainly thinks so. In the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, it predicts that inflation will “gradually return to the target band within 2024-25” – that is, by no later than the June quarter of 2025, six months earlier than envisaged by the RBA.

The CBA Chief Economist Stephen Halmarick attracted a lot of attention just before Christmas, forecasting that the RBA would cut its cash rate by 75 basis points in the second half of 2024, and by another 75 basis points during 2025 (ie, to 2.85%) as a result of inflation falling under 3% by the end of this year, rather than by the end of 2025.

Treasury and the CBA may be right – although I’m personally skeptical inflation will fall that quickly, especially with renewed pressure on global supply chains as shipping companies avoid using the Suez Canal, and the likelihood of a surge in banana prices similar to the one which occurred in 2011 (as a result of the floods in Far North Queensland), as well as continuing pressure on housing costs with net migration coming down only slowly from this year’s likely total of around 500,000.

The RBA might find itself under pressure to cut rates, even if inflation evolves in line with its forecasts, if lower US rates combine with persistently high commodity prices to prompt significant further upward pressure on the A$ (which would of course, all else being equal, be a disinflationary force in itself). But given what I think is the poor prognosis for the Chinese economy – the major market for Australian commodity exports – I would expect commodity prices to decline over the course of next year, probably neutralizing the impact of lower US interest rates and a weaker US dollar.

To re-iterate, I think the RBA has chosen a slightly different path for returning inflation to its target than its peers. Emphatically, I’m not criticizing them for having done so. Indeed, they haven’t actually said that they’re following a different path from their peers – that’s just my inference. But (if I’m right) it does mean that the RBA will likely follow a slightly different path on the way down, just as it has on the way up.